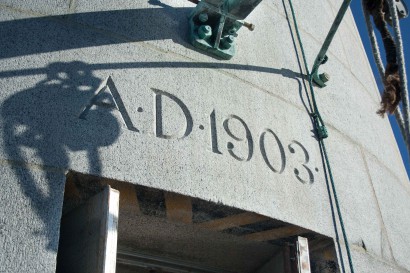

Boston Harbor, MA ~ 1903

Our reclaimed oak flooring was just installed at the most wildly inaccessible jobsite we’ve ever visited. It’s also one of the most beautiful. In 2013, Lynn and Dave Waller purchased the Graves Island Light Station from the federal government…without even owning a boat. One year and countless hours of comically challenging workdays later, the Wallers are nearing completion of their heroic lighthouse restoration.

This October, Lynn and Dave invited Longleaf Lumber on a Graves Island visit to survey the reclaimed oak flooring installation. The journey was an inspiring daytrip to the outer reaches of Boston Harbor and an eye-opening perspective on a ‘challenging renovation.’

reaching the lighthouse

Situated nine miles from downtown Boston, at the outer reaches of the harbor, is the Graves Island Light Station. Each trip to the island begins in a small, 26′ boat docked at Winthrop Marina. Each day’s work equipment and supplies are loaded into the boat, motored past Logan Airport, around Deer Island, and to a mooring seventy yards or so from the lighthouse. Supplies are then ferried from the boat to the lower ladder via small dinghy.

During each circuit, materials (even reclaimed oak flooring) are hoisted onto the lighthouse deck via a hand-operated pully. To operate the hoist, a worker (or volunteer, in our case) climbs from the inflatable dinghy onto the lower ladder for the 20′ climb to the lighthouse deck.

After all of the equipment and workers are ferried from the boat to the deck, the process begins anew as materials are loaded into buckets and bags to be hoisted to the lighthouse door, in hand-over-hand fashion. To operate that hoist, workers must first climb a second 20′ ladder to the building entrance.

Working at the lighthouse puts landlocked construction work into perspective. After the departure of the Wallers’ hired work barge, which featured a crane and supported the sandblasting, powerwashing, and deck repair portions of the renovation, the project has been supplied one yank of the rope at a time. Utility lumber, paint, water, flooring, power tools, gasoline, and people have since been hoisted onto the deck and into the lighthouse.

The lighthouse

The building is serviced by a 20′ ladder (which hangs into the ocean most of the day) leading to a small deck where equipment can be stored in the open or under cover of a small shed. From the deck, another 20′ ladder reaches to the lighthouse door.

The reservoirs were originally intended to store compressed air for the foghorn and fresh water for the light attendant. Eventually filled with diesel for electricity generation, the cisterns are now being emptied with – you guessed it – a bucket and a rope. After removing the rancid mixture of diesel, water, and dirt, workers lower each five-gallon bucket to the deck, then to the dinghy, and finally transfer the slop to mainland Boston for responsible disposal.

The top floor features thick metal walls and thematically-sensitive portholes recently installed by the Wallers. The interior walls, staircases, and ceiling beams have all been repainted with heavy-duty epoxy-based marine paint, and the windows have all been replaced with new, weather-appropriate assemblies.

The most beautiful room in the tower is, expectedly, the beacon room, which is completely encased in diamond-pattern curved glass walls and surveys the sweeping Massachusetts coastline from Cohasset, over downtown Boston, and all the way to Gloucester.

our reclaimed oak floors

Part of the restoration process at Graves Island involves repairing the damaged wooden floors. Built mostly of thick plate metal, the lighthouse’s interior does include three stories of oak flooring, much of which had been destroyed by marine weather and total neglect. Looking to maintain the original character of the structure, the Wallers reached out to Longleaf for replacement floorboards, freshly milled from reclaimed oak barn beams. Their use of reclaimed building materials in the project fit perfectly within the project’s necessarily sustainable ethos; the lighthouse will be solar-powered and will desalinate its own water.

We don’t generally toot our own foghorn, but the Longleaf reclaimed oak flooring blows the original quartersawn oak floors right out of the water. Dave has promised to send us photos of the finished floor, but the last we’ve heard from him, he was “Having trouble finding a floor guy to come out with his sander.”

We’re lucky to have been able to visit the Wallers’ new restoration project, and we’re hoping the station is opened to the public sometime after work is finished, even if in a limited capacity. The restoration’s spirit of adventure, ethos of sustainability, and caretaking of history are certainly something to be admired and shared.